For

almost 200 years, Pennsylvania and its penal institutions have been leaders in

prison innovation and reform. Born in

1818, Western State Penitentiary (known as SCI-Pittsburgh since 1959) not only

shares in the early history of our city and state, but claims a legacy of

leadership and progress in penology and reforms that would set national and

international standards for over a century.

Following

the Revolution, Americans who had fought for “life, liberty, and the pursuit of

happiness” now sought a more enlightened approach to imprisonment. Pennsylvania ,

through the Prison Society of Philadelphia, was at the forefront of penal

reform. Earlier jails in Philadelphia

had already challenged long-held penological practice, which had evolved little

since medieval times.

Through

the guidance of the Prison Society, Pennsylvania legislators approved the

construction of two state penitentiaries in 1818: Eastern State, in

Philadelphia, and Western State, in Allegheny, which would later be annexed by

Pittsburgh and known as the North Side.

The

design of these prisons was to follow the new “Pennsylvania System,” the

brainchild of the Prison Society. Rather

than simply boarding prisoners like animals in a stable, the Pennsylvania

System sought to reform inmates through labor and religious counseling while

housing them in solitary confinement.

Inmates were to reflect on their misdeeds, exhibiting their penitence,

leading to the term “penitentiary.”

Through this indoctrination by work and religion, it was hoped to

convert criminals into law-abiding, functional Americans.

The “First” Western State Penitentiary (1818-1836)

|

The first Western State Penitentiary,

1818-1836

|

Following

passage of legislation in 1818, noted American architect William Strickland was

selected to design the Western State Penitentiary. Construction began immediately at what is now

the site of the National Aviary on Pittsburgh’s North Side. Work continued even after the first inmates arrived in 1826 and terminated the following year. (Eastern State would not open until 1829).

Little

is known about inmate life during this period.

Inmate labor most often consisted of sewing for female inmates and the

construction of shoes by male inmates, all of which was done in solitary

confinement. Silence and minimal human

contact was also strictly enforced.

Western

State contained 190 solitary confinement cells, measuring eight by twelve feet

each. The exterior resembled a Norman

castle, with walls three feet thick, and a layout resembling a wagon wheel (for

which Eastern State has since become famous).

Despite its cost at $178,206 and strict adherence to the new

Pennsylvania System of penology, the cells were deemed too small and dark for

inmate labor in solitary confinement, and orders were given to demolish the

cells and construct larger ones on the same site.

The “Second” Western State Penitentiary (1836-1884)

|

The “second” Western State Penitentiary,

as it appeared c. 1845

|

Following

the decision to rebuild the cells, William Haviland, who had designed the Eastern

State Penitentiary, was selected to redesign Western State. Instead of seven radiating wings, as at

Eastern State, Western State would eventually have (after further expansions)

three main wings connected to a main building, containing in all 230

cells.

The slow growth of

the prison population in the years prior to the Civil War allowed Western

Penitentiary to continue the practice of solitary confinement without any

concerns about overcrowding. In the

ensuing years, however, steady increases in the population prompted further

development. The prison expanded to contain 324 cells and had added a new

hospital building by 1865, along with a new building for housing the female

inmates (with 24 cells) in 1870. The new

cells were enlarged to seven feet-ten inches by fifteen feet, with gas lights,

a four-inch slit-window, and steam heating.

Major changes in operations and inmate life occurred in 1869 with the appointment of Edward “Sandy” Wright as warden. Wright eliminated the system of constant solitary confinement, allowing inmates to congregate for work, meals, worship, for greater production efficiency and mental health. Additionally, he implemented early release for good behavior, a forerunner of today’s parole system.

Even

with this series of expansions, the inmate population continued to outpace

structural growth. Coupled with the

growing neighborhood around it in the 1870’s and their distaste for convicted

neighbors, Western State Penitentiary began looking for a new home.

“Riverside”, the modern home of Western State

Penitentiary, aka SCI-Pittsburgh (1878- today)

|

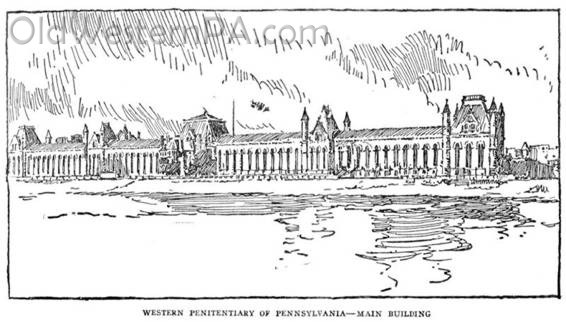

| This view shows the north end, c. 1906-1911. |

The

operators of the Western House of Refuge had abandoned the site, believing it

suffered from poor sanitary conditions, and instead creating the Morganza

Reform School in Washington County.

After

purchasing the site in 1878, the process of transferring inmates to the

building began, even while architect E.M. Butz commenced renovations and

expansions. Inmate laborers worked

through 1892, erecting the new south wing, renovating the

administration building and constructing a new attached home for Warden

Wright. When completed, it was the most

modern prison in the world, boasting 1,280 cells in two wings, each five tiers

high in the new Auburn style congregate

system. It was the first prison in the

world to have gang locks, electric lights, running water, heat and exhaust

ventilation, and a toilet in each cell.

In

addition to updated physical features, Western State Penitentiary would make

social advances in welcoming Dorothea Dix, the famed activist whose efforts

created the first generation of mental asylums in the United States. Working with Dix, Western State Penitentiary

would be a pioneer in addressing mentally ill inmates, who would be among the

first patients at Dixmont State Hospital, established just 10 miles downriver.

The new location also allowed for the growth of inmate

labor. Industrialization brought

mechanized labor behind the walls.

Inmate industries expanded to include making shoes, brooms, chains,

cigars, weaving mats, and leasing labor to outside industries.

Inmate labor became so successful that its profits spared taxpayers the majority of incarceration costs. However, following the passage of repressive legislation in 1898, inmate labor was severely curbed and relegated to supporting prison operations and producing goods for the state, such as the production of automobile license plates.

Inmate labor became so successful that its profits spared taxpayers the majority of incarceration costs. However, following the passage of repressive legislation in 1898, inmate labor was severely curbed and relegated to supporting prison operations and producing goods for the state, such as the production of automobile license plates.

Throughout the twentieth century, Western State Penitentiary would continue to be the western cornerstone of Pennsylvania’s prisons. Just as Pennsylvania’s penal facilities grew and shifted, their governance moved from a sub-bureau of the Department of Welfare to the Bureau of Corrections under the Department of Justice, and finally as an independent Department of Corrections. Western State Penitentiary adapted as well, changing its name to SCI-Pittsburgh in 1955, adding two new cell blocks in the 1980’s, and Riverside CCC.

Even after closing in 2005, SCI-Pittsburgh would surge back

to life two years later. SCI-Pittsburgh’s

location allows inmates to receive treatment in Pittsburgh’s

internationally-known healthcare systems.

Additionally, SCI-Pittsburgh continues to lead in innovation and direct

inmate care.

UPDATE:

In 2017 state officials decided to close SCI Pittsburgh. While the site has been used as a film location for several productions, in February 2024 it was decided to demolish this historic structure. As with many of Western Pennsylvania’s significant structures, Western State Penitentiary will soon belong to the ages.